A disturbing report was issued by the Center for American Progress about LGBTI discrimination. 1 in 4 LGBT people report experiencing discrimination in 2016.

“This is clearly unacceptable and we must eliminate the Kentucky Religious Freedom Act. We call on the Kentucky Supreme Court to overturn this legislation which is effectively a license to discriminate,” stated Jordan Palmer, secretary-general of Kentucky Equality Federation, Marriage Equality Kentucky, Southeastern Kentucky Stop Hate Group, Be Proud – Western Kentucky, Kentucky HIV Advocacy Campaign, Kentucky Equal Ballot Access, and others combined together in the Earth Equality Alliance.

Over the past decade, the nation has made unprecedented progress toward LGBTI equality. But to date, neither the federal government nor most states (including the Commonwealth of Kentucky – http://kentucky.gov) have explicit statutory nondiscrimination laws protecting people on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. LGBTI people still face widespread discrimination: Between 11 percent and 28 percent of LGBTI workers report losing a promotion simply because of their sexual orientation, and 27 percent of transgender workers report being fired, not hired, or denied a promotion in the past year. Discrimination also routinely affects LGBTI people beyond the workplace, sometimes costing them their homes, access to education, and even the ability to engage in public life.

Data from a nationally representative survey of LGBTI people conducted by CAP shows that 25.2 percent of LGBTI respondents

Among people who experienced sexual orientation- or gender-identity-based discrimination in the past year:

- 68.5 percent reported that discrimination at least somewhat negatively affected their psychological well-being.

- 43.7 percent reported that discrimination negatively impacted their physical well-being.

- 47.7 percent reported that discrimination negatively impacted their spiritual well-being.

- 38.5 percent reported discrimination negatively impacted their school environment.

- 52.8 percent reported that discrimination negatively impacted their work environment.

- 56.6

report

Unseen harms

LGBTI people who don’t experience overt discrimination, such as being fired from a job, may still find that the threat of it shapes their lives in subtle but profound ways. David M., a gay man, works at a Fortune 500 company with a formal, written nondiscrimination policy. “I couldn’t be fired for being gay,” he said. But David went on to explain, “When partners at the firm invite straight men to squash or drinks, they don’t invite the women or gay men. I’m being passed over for opportunities that could lead to being promoted.”

“I’m trying to minimize the bias against me by changing my presentation in the corporate world,” he added. “I lower my voice in meetings to make it sound less feminine and avoid wearing anything but a black suit. … When you’re perceived as feminine—whether you’re a woman or a gay man—you get excluded from relationships that improve your career.”

David is not alone. Survey findings and related interviews show that LGBTI people hide personal relationships, delay health care, change the way they dress, and take other steps to alter their lives because they could be discriminated against.

Maria S., a lesbian who lives in North Carolina, described a long commute from her home in Durham to a different town where she works. She makes the drive every day so that she can live in a city that’s friendly to LGBTI people. She loves her job, but she’s not out to her boss. “I wonder whether I would be let go if the higher-ups knew about my sexuality,” she says.

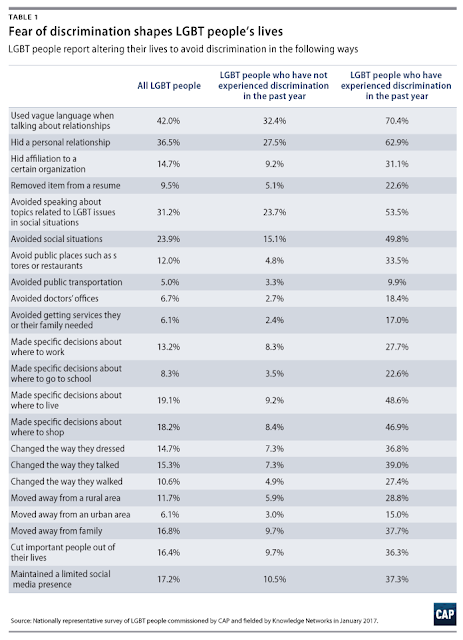

CAP’s research shows that stories such as Maria’s and David’s are common. The below table shows the percentage of LGBTI people who report changing their lives in a variety of ways in order to avoid discrimination.

|

| Click to make larger. |

As Table 1 shows, LGBTI people who’ve experienced discrimination in the past year are significantly more likely to alter their lives for fear of discrimination, even deciding where to live and work because of it, suggesting that there are lasting consequences for victims of discrimination. Yet findings also support the contention that LGBTI people do not need to have experienced discrimination in order to act in ways that help them avoid it, which is in line with empirical evidence on a component of minority stress theory: expectations of rejection.

Not only can

Unique vulnerabilities in the workplace

Within the LGBTI community, people who were vulnerable to discrimination across multiple identities reported uniquely high rates of avoidance behaviors.

In particular, LGBTI people of color were more likely to hide their sexual orientation and gender identity from employers, with 12

Similarly, 18.7 percent of 18- to 24-year-old LGBTI respondents reported removing items from their resumes—in comparison to 7.9 percent of 35- to 44-year-olds.

Meanwhile, 15.5 percent of disabled LGBTI respondents reported removing items from their resume—in comparison to 7.3 percent of

Unique vulnerabilities in the public square

Discrimination, harassment, and violence against LGBTI people—especially transgender people—has always been common in places of public accommodation, such as hotels, restaurants, or government offices. The 2015 United States Transgender Survey found that, among transgender people who visited a place of public accommodation where

That year, more than 30 bills specifically targeting transgender people’s access to public accommodations were introduced in state legislatures across the country. This survey asked transgender respondents whether they had avoided places of public accommodation from January 2016 through January 2017, during a nationwide attack on transgender people’s rights.

Among transgender survey respondents:

- 25.7 percent reported avoiding public places such as stores and restaurants, versus 9.9 percent of

cisgender - 10.9 percent reported avoiding public transportation, versus 4.1 percent of

cisgender - 11.9 percent avoided getting

services cisgender - 26.7 percent made specific decisions about where to shop, versus 6.6 percent of

cisgender

Disabled LGBTI people were also significantly more likely to avoid public places than their

- 20.4 percent reported avoiding public places such as stores and restaurants, versus 9.1 percent of

nondisabled - 8.8 percent reported avoiding public transportation, versus 3.6 percent of

nondisabled - 14.7 percent avoided getting

services nondisabled - 25.7 percent made specific decisions about where to shop, versus 15.4 percent of

nondisabled

This is likely because, in addition to the risk of anti-LGBTI harassment and discrimination, LGBTI people with disabilities contend with inaccessible public spaces. For example, many transit agencies fail to comply with

Unique vulnerabilities in health care

In 2010, more than half of LGBTI people reported being discriminated against by a health care providers and more than 25 percent of transgender respondents reported being refused medical care outright. Since then, LGBTI people have gained protections from

Unsurprisingly, people in these vulnerable groups are especially likely to avoid doctor’s offices, postponing both preventative and needed medical care:

- 23.5 percent of transgender respondents avoided doctors’ offices in the past year, versus 4.4 percent of

cisgender - 13.7 percent of disabled LGBTI respondents avoided doctors’ offices in the past year, versus 4.2 percent of

nondisabled - 10.3 percent of LGBTI people of color avoided doctors’ offices in the past year, versus 4.2 percent of white LGBTI respondents

These findings are consistent with research that has also identified patterns of health care discrimination against people of color and disabled people. For example, one survey of health care practices in five major cities found that more than one in five practices were inaccessible to patients who used wheelchairs.

A call to action

To ensure that civil rights laws explicitly protect LGBTI people, Congress and all States should pass an Equality Act, a comprehensive bill banning discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, public accommodations, housing, credit, and federal funding, among other provisions.

*Authors’ note: All names have been changed out of respect for interviewees’ privacy.

Methodology

To conduct this study, CAP commissioned and designed a survey, fielded by Knowledge Networks, which surveyed 1,864 individuals about their experiences with health insurance and health care. Among the respondents, 857 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender, while 1,007 identified as heterosexual and cisgender/

Separate from the quantitative survey, the authors solicited stories exploring the impact of discrimination on LGBT people’s lives. Using social media platforms, the study authors requested volunteers to anonymously recount personal experiences of changing their behavior or making other adjustments to their daily lives to prevent experiencing discrimination. Interviews were conducted by one of the study authors and names were changed to protect the identity of the interviewee.

Additional information about study methods and materials are available from the authors.